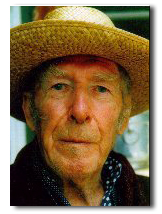

mark o'connor - australian poet

Tribute to A.D. Hope

In 2000 Australia lost two huge oaks from its literary canopy: the poets Judith Wright and A D Hope. At that time Mark O'Connor was being interviewed about the Olympics on the ABC's Radio National Breakfast Program as he followed the Olympic Torch around Australia, so he turned two of these interviews into impromptu obituaries for Wright and Hope. (He had been associated with Judith Wright in environmental groups such as Australians for an Ecologically Sustainable Population, of which she was Patron and he was National Vice President, and he had been a friend of Hope's for 30 years.)

The following is an extract from the transcript of a later program, Mark's tribute to A D Hope, titled A D Hope, Poet of Love and Mortality. This was broadcast in the Radio National Encounter series on Sunday 31 December 2000.

A D Hope: Poet of Love and Morality

By Mark O'Connor

Man's need for certainty is a disease past cure.

Where are those fixed world-pictures of the past

Which, as they changed, gave place

to others as sure?

Christmas is over, Christmas is over at last!

A D Hope.

ALEC HOPE was no saint, but he is an outstanding example of a person who lived the stages of his life with increasing grace. Some 25 years ago, when his popular image was that of a coarsely sexual writer, a quite unliterary girlfriend of mine met him at a party and had a long chat with him. Afterwards she said, 'What a lovely old man. I'd just like to take him home and install him as my grandfather!

Hope aged well, and with acceptance. It is not every agnostic or half-believer who can accept Lucretius's advice to turn calmly home like a well-fed guest from the banquet of life:

I too must die---nor would I be reborn,

But offer my death to quicken other lives,

Trusting, if in my turn I bring my song,

Deep underground my shade may taste that strong

Black honey from which alone our art revives,

And share its resurrection with the corn

Hope's life story, like Judith Wright's, demonstrates something that is often forgotten. A 'good poet' may be simply someone who, on the page, is inventive, observant, and skilled with words; but a 'great poet' is something more. He or she is usually someone who is also good at life---that is, someone who has found original and personal answers to the problems of being human.

The Audens, Hopes, Les Murrays, Bruce Dawes, Gwen Harwoods and Judith Wrights may not always be as wonderful in real life as in their poems, but they could not have projected such personal largeness into their poems if they had not possessed much of it in life. It is hard to convey the gentle grace Hope had in later life. His wit was kindly, situational rather than epigrammatic. One story must suffice.

Twenty years ago when Hope was in his 70s he was waiting to speak at a literary conference. The MC proved to be a younger poet with a fine voice and a thinly concealed belief that this public attention would have been better directed to his own vibrantly new group than to this ancient personage. The speech of introduction went on and on. Superficially a commendation of Hope, in fact it was short on literary appreciation and full of somewhat slighting references to him as a 'senior' or as our oldest poet. The audience grew restive. When Hope was finally permitted to toddle to the microphone, most looked for him to retaliate; but he appeared to have heard only compliments. 'As you will have gathered from the delightful commercial we've just heard', he began, 'I've been dead now for some years.

Hope often felt he could sense the 'hum' of a benign universe. Indeed an acceptance of the variousness of life, and of the need to let the tares grow among the grain, breathes through many of his poems:

The City of God is built like other cities.

Judas negotiates the loans you float.

You will meet Caiaphas upon committees.

You will be glad of Pilate's casting vote.

The program discusses Hope's remarkable ability, which he explains in his book The New Cratylus, to do consistently what Coleridge may have done only once---to compile drafts of poems in his sleep. Though he rejected or heavily revised most such drafts, he regarded the contribution of his 'dreamworkers' as essential. Because of his sexually explicit works Hope was seen as a great sensualist. Yet the program shows that within the devastating impersonality of sex, he sees always a glimmer of love. As he ripened into one of the great love poets of the century, love often seemed to him a religious mystery, sex its sacrament. He produced haunting lines like 'You near me, you always, you watchful and invisible one'

But it was the nature of the universe that he sought hardest to grasp in verse. Hope realized that recent advances in astronomy, geology, and biology have created a new picture of the world---the most complete, complex, and structured picture that has been available to any poet since the Middle Ages. He certainly understood the pull of religious faith. His line 'Man's need for certainty is a disease past cure' implies that it takes strength to live with a mysterious universe, to admit that one may live and die in times when its answers are not known. Hope was scientist enough to do that---rather like his colleague Manning Clark, dying with 'a shy hope of immortality'.

Like Wallace-Crabbe Hope conceded at the end that the strongest statement he could make would have to be surrounded by question marks:

Do other beings inhabit our biosphere

Whose life is one and whole? I cannot tell.

I only know at moments everywhere

I sense their presences in earth and air...

From The Wild Bees